Computational Learning in Games

U of St. Gallen and Hasler Foundation funded work on RL in economic games

Companies increasingly employ machine learning techniques in their decision-making. In digital markets in particular, such algorithms are a key factor in ensuring a firm’s success. But despite their widespread adoption, we know very little about how algorithms interact and how they can influence economic outcomes. In this project, we investigate the behavior of interacting reinforcement learning algorithms in standard economic games and develop a software environment in which the behavior of learners in mathematical games can be studied.

Funding by the University of St. Gallens Basic Research Fund allowed us to lay the groundwork by implementing simple Q-learning algorithms in repeated pricing games with imperfect competition. In Eschenbaum et al. (2021), we apply our software to study the ability of learners to tacitly collude in Bertrand-style games. A recent literature finds that algorithms consistently learn to collude, however existing work reports results solely based on performance in the training environment. In practice, firms train their algorithms offline before using them, and the training and market environment differ. To study the possibility for learners to extrapolate collusive policies to the market environment, we develop a formal, general framework to guide the analysis of reinforcement learners in economic games.

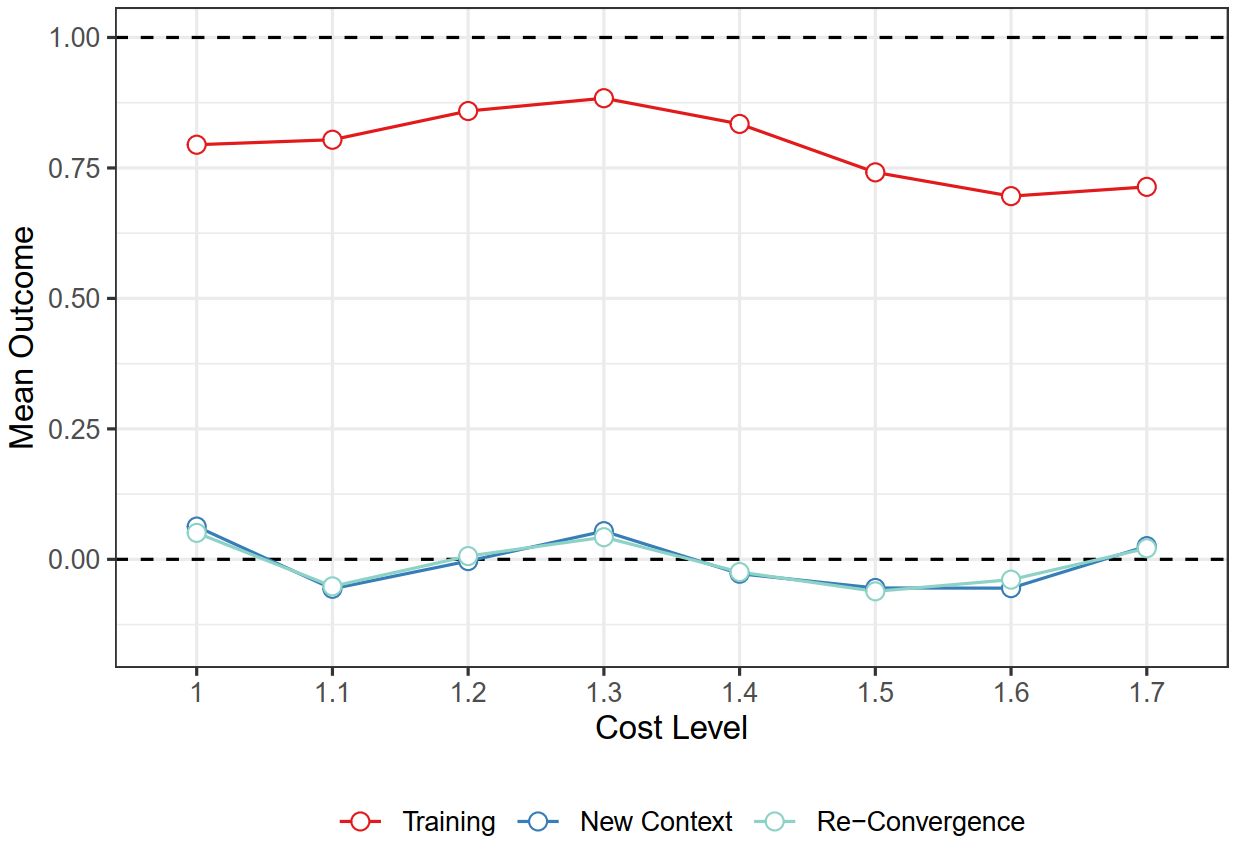

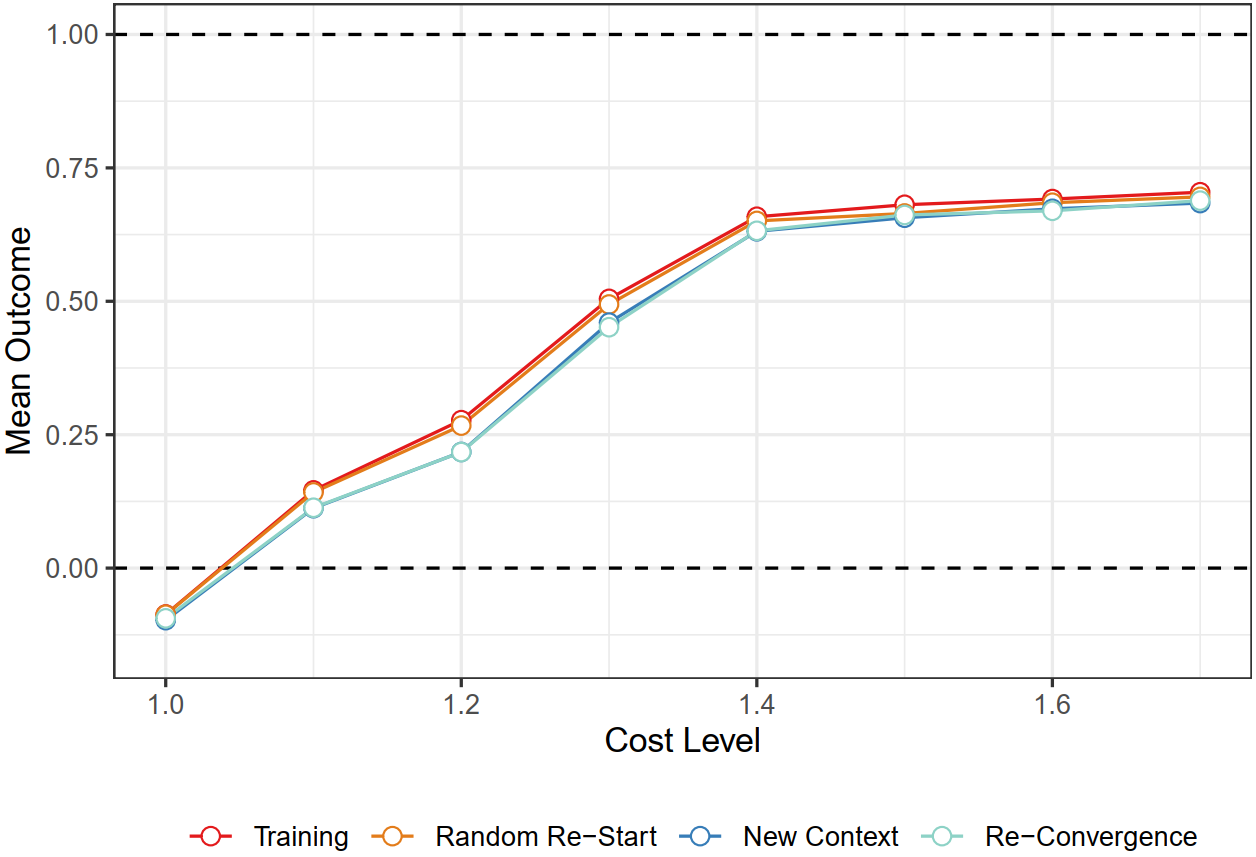

We first show that while algorithmic collusion consistently arises during training, in testing contexts collusion vanishes. This does not change with further iterations. Instead, we observe evidence of Nash play of the underlying stage game. This shows that algorithmic collusion is not robust to changes in the environment, and performance during training is no indication of outcome in the market.

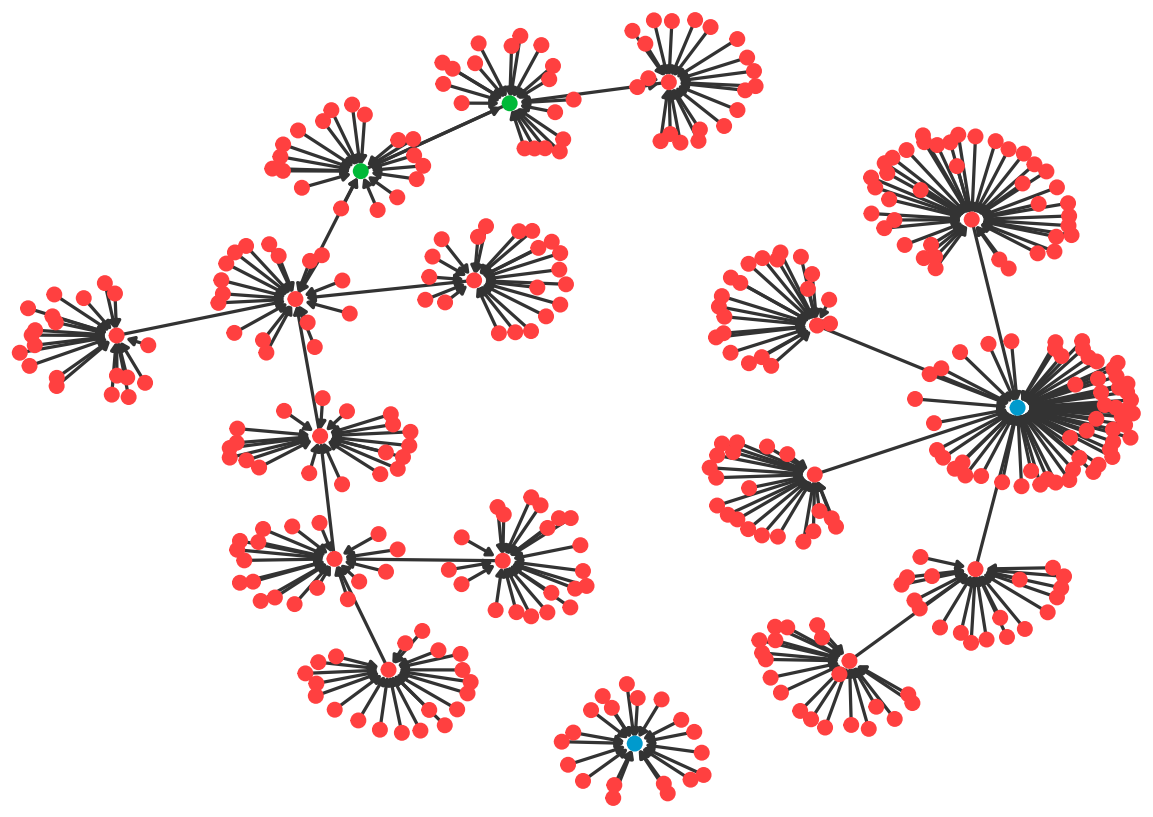

It turns out that the reason for this breakdown of collusion is an overfitting to rival strategies from training, and more broadly the high-dimensionality of the strategy space. Even pairs of jointly converged policies that lead to the same collusive outcome during training can be vastly different, and all generally have multiple different stable outcomes that can be played. It is unsurprising that a given policy learnt during training then does not lead to the same outcome when playing against a policy different to the rival policy from training.

Our analysis suggests that a key driving force of algorithmic collusion in practice is coordination of algorithm design. Firms in practice may be able to successfully achieve algorithmic (tacit) collusion by coordinating on high-level ideas for the implementation of learning algorithms.

Further funding by the Hasler Foundation has allowed us to develop a comprehensive integration of game theory and machine learning. We have integrated a programmatic, modular framework of mathematical games called open games with machine learning libraries, in particular Ray and Rlib. The repository for open games can be found here, for the underlying re-development of game theory called compositional game theory see Ghani et al, 2018. This software allows a modular construction and combination of complex games with separately scripted cutting-edge RL algorithms.

Project materials:

- Nicolas Eschenbaum, Filip Mellgren, and Philipp Zahn. Robust Algorithmic Collusion (WP). 2021.